Spooky true story: Detroit’s Eastern Market Sheds are built on top of the old Russell Street Cemetery

*PLEASE NOTE: This paper is not intended to be a scholarly dissertation. It is a true story of Detroit history intended for the general public. This article will be periodically updated as new information crops up. As stated at the end of the article, please fact-check me and feel free to email me at place313 at gmail dot com and let me know if anything needs to be updated for greater accuracy. Thank you! *

I first heard this story a few years ago from my friend, Lonni Thomas. Since then, I’ve scoured libraries, old newspapers and online for more information.

Eastern Market, the largest historic public market in the USA, consists of a series of Sheds, essentially a row of large indoor consumer buildings running North to South along the eastside of Russell Street in Detroit, Michigan. The Sheds host vibrant weekly markets and lively annual events like the Detroit Festival of Books, Detroit Fall Beer Festival, Flower Day, etc.

What many people don’t know:

These Sheds are built on top of the old Russell Street Cemetery (1834-1882) and where a portion of the old prison, Detroit House of Corrections, aka: DeHoCo, used to be located (1861-1931).

This is a largely hidden and unknown spooky true tale of Detroit history.

Let’s take a look back into the mysterious pre-Eastern Market history of Old Detroit.

Essential Background Details on the creation and dismantling of the Russell Street Cemetery

In the 1800’s, Detroit was not the sprawling cosmopolitan city it is today. It had a more rough-and-tumble frontier town feel to it.

According to Gen. Palmer, there was a town water pump at the foot of Randolph Street and tramps and thieves used to be whipped at the public whipping post on Woodward Avenue.

By 1834, the city had around 5,000 residents when the Russell Street Cemetery was established. Michigan was a vast territory at that time and didn’t even become a state until 1837.

Russell Street Cemetery was open 1834-1882 in what’s now known as the Eastern Market neighborhood of Detroit. It was located along Russell Street roughly from modern day Gratiot to Eliot. It was also known as the Second City Cemetery.

The First City Cemetery, often called Clinton Park Cemetery, was created May 29, 1827, on land the city had purchased from Col. Antoine Beaubien’s ribbon farm. It was a long, narrow, 30-foot wide plot of land stretching from Gratiot Ave and Clinton St down to Jefferson Ave. Supposedly, Gen. Friend Palmer’s father was the first person buried here. The cemetery closed to further interments in 1854 and was officially vacated by November 12, 1869. So, yes, it did exist concurrently for a few decades with Russell.

On May 31, 1834, the city of Detroit purchased 55 acres of farmland from the probate estate of Charles Guoin for the then-handsome sum of $2,010. The Guoin family had farmed this land for almost 100 years, since 1742. Charles Frances Guoin was born February 2, 1755 and died sometime between 1830-32. At some point, Charles had relations with Little Snipe, a local Pottawatomie woman, and they had a daughter named White Feather (Marie LaVoy).

A few months after the purchase, in August 1834, 38 acres became the Russell Street Cemetery. This decision was made by the Detroit Common Council. This area supposedly (although not conclusively) was bound by modern-day Russell Street, Eliot Street, the Freeway, Gratiot Ave, and an undefined eastern boundary. At its peak, supposedly, some 10,000-15,000 graves are estimated to have been here but nobody knows for sure because various records have either been lost or were never kept in the first place.

By August 1834, the burials at Russell Street Cemetery were numerous because Detroit was in the throes of a second cholera epidemic, which killed an eighth of the city’s population. Cholera epidemics hit Detroit hard in 1832 and 1834 and “congested the graveyards,” (Burton, page 969). There were most likely multiple bodies per grave in many instances.

In those days, the City Sexton was the title of the official gravedigger and person in charge of a cemetery. Originally, the City Sexton was tasked with selling plots (half or full) at the Russell Street Cemetery to people, which ranged in cost from five to ten dollars. The city of Detroit created the office of City Sexton on March 17, 1829 and it was abolished in 1879.

The first sexton of Detroit was Israel Noble. He was nominated by the mayor, then appointed by Common Council. He served as Sexton from 1829-32, then 1835-49. Noble, incongruously detached from living up to the meaning of his last name, supposedly sold Russell Street Cemetery lots under the table for some side cash, hence the mysterious lack of “official records”.

Noble was also, at one point, the keeper of the lighthouse in Monroe, Michigan.

In 1841, Mt. Elliott Cemetery opened, which helped divert burials from Russell Street.

In 1842, Dr. George Russell built a “Contagious Disease Hospital” on the potter’s field area of the Russell Street Cemetery. In reality, it was a small rickety shed. However, it may have been the first building in the Midwest dedicated to treating contagious diseases. The shed didn’t last long.

Then in 1846, the posh new Elmwood Cemetery opened, which served to briefly alleviate the overcrowding of the Russell Street Cemetery.

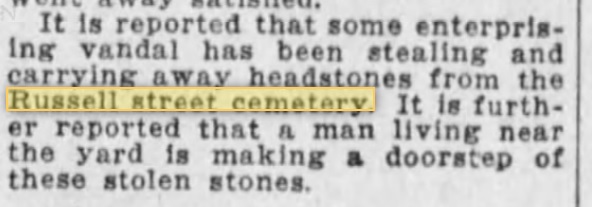

As the years went by, the city notoriously failed to maintain the Russell Street Cemetery and it became desperately rundown. One report stated that “People would steal tombstones and use them as doorsteps and beer counters,” (Lazar, page 15).

April 10, 1855, the Health Committee advises Detroit Common Council that no more burials should be allowed at Russell Street Cemetery. This was 27 years before the cemetery was officially closed in 1882, so there was definitely a long history of the cemetery being wretched and unkempt.

In 1857, Mayor Ledyard publicly called the cemetery a “disgrace” and wanted it torn down. Also, in May 1857, modern-day Division Street was constructed and cut right through the cemetery.

On July 6, 1861, a prison was built on a part of the cemetery (area roughly bound by Russell, Riopelle, Alfred, and Wilkins) called the Detroit House of Corrections (aka: DeHoCo). It remained there until 1931 when the prison was relocated 30 miles west to the city of Plymouth, Michigan.

In 1868, modern-day Winder Street opened through the cemetery.

Fed up with the abysmal conditions of the cemetery, on April 20, 1869, Detroit city council ordered that no more bodies be buried at Russell Street Cemetery. Over the next 13 years, thousands of corpses were periodically transferred to Elmwood, Mt. Elliott, and the new 250-acre “rural cemetery” called Woodmere, which was formally dedicated July 14, 1869.

Woodmere Cemetery was located only a mere 8 miles west of Russell Street Cemetery, but at that time was considered rural countryside. Prior to being a cemetery, Woodmere was a Revolutionary War-era shipyard where several ships were built.

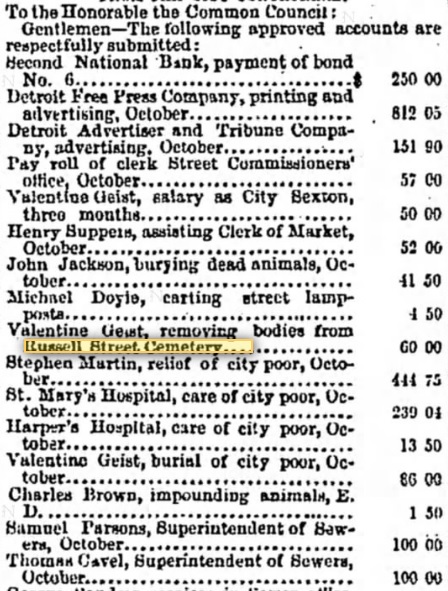

The City Sexton at the time, a German man named Valentine Geist, spearheaded the transfer of bodies from Russell Street Cemetery to Woodmere. He lived 1824-95 and served as Sexton in the years 1864, 1871-74, 1878. He also ran an undertaking business on Monroe Street downtown. He’s buried at Elmwood.

Around about 1870, the first makeshift Hay and Wood Market was built on Russell Street (between Adelaide and Division) and some independent street vendors started selling farm-grown produce from their own carts and wagons in proto-Eastern Market along Russell Street near the cemetery.

However, over the decade (1870-1880), nothing much happened at the Russell Street Cemetery except the tombstones became mossgrown, the cemetery became weedy and neglected, and people used to mess around in the cemetery at all hours of the day and night. A sad trend throughout history is that old, neglected cemeteries tend to become general dumping grounds.

Then on May 14, 1879, the Circuit Court ordered the cemetery to be officially vacated. Various contracts were issued for the removal and reinternment of the remaining cadavers in other cemeteries: Woodmere, Elmwood, Mt. Elliott, and elsewhere. This task was coordinated by the Board of Public Works. One of the few names mentioned in the newspaper, a man named John Griswold, was reinterred at Woodmere.

One wave, some 1,493 caskets, were removed in 1880 and re-buried at the City Hospital grounds in Grosse Pointe. In 1881, another 1,668 remains were shipped out. Then in early 1882, some 1,357 bodies were relocated. Various numbers are given in the newspapers, but the final destination of the caskets is not always given, thus, it’s impossible to know for sure what bodies went where.

By 1882, all known remains were removed from Russell Street Cemetery.

The Unclaimed Dead (or what happened next?)

Conner’s Creek, named for Henry Conner, existed from 1840-1925, according to Dr. Krepps (page 21 of her report). The Algonquin lived here prior to city development.

In 1872, Antoine Dubay owned a farm here. The deed was purchased from him on August 24, 1872 by Frederick Ruehle (sometimes spelled Ruelle). Frederick quickly turned around and sold the 34-acre property to the city of Detroit on October 18, 1872. He purchased the 34 acres for $3,000 and conveniently sold it less than two months later for $6,000.

At the time, this property was in the neighboring city of Grosse Pointe, which is where Detroit wanted to build a City Hospital for smallpox victims (aka: the Grosse Pointe Pest House), but the deal never fully went through. A structure was built here but was never used as a hospital.

Instead, a large corner of the farm became the Conner Creek Cemetery (aka: Third City Cemetery or the City Hospital Grounds, as it was commonly called at the time). It was used to re-bury the unclaimed/unidentified bodies from the Russell Street Cemetery.

The cemetery was dedicated August 27, 1880. It eventually contained around 4,500 bodies, which were (most likely) transferred via wagon some five miles NE up Gratiot Ave to Harper Ave and over to Conner Creek. Between 1880-1882, some 4,500 bodies were taken from Russell Street Cemetery to Conner Creek Cemetery.

Gratiot Avenue, at that time called Fort Gratiot Road, was constructed between 1829-1833.

In November 1881, the city of Detroit did build a pest house structure on the SW corner of Conner at Olga Street, however, it was never used because Grosse Pointe effectively blocked the construction of a pest house (smallpox hospital) in their town. So, the city rented it to a farmer, whose name is listed sometimes as August Stahlman, other times as August Schultz, and he ended up living inside the 24 x 76 building for a few decades.

The structure burned down in 1923. Currently, the Wayne County Community College Eastern Campus is located where this structure used to be.

Furthermore, a playground called the Conner Playfield (located on Conner, north of Harper) was built over a portion of the cemetery at some point, possibly in the 1930’s or early 1940’s.

The Conner Creek Cemetery was largely forgotten for decades until October 6, 1950 when utility workers accidentally dug up some corpses and a tombstone across from a house at 6020 Gunston. During Virginia Clohset’s discovery interview of Ida and Pasquale Gianfermi (residents of 6020 Gunston St), Ida said she vividly recalled the 1950 dig and said that spectators took bones home as souvenirs.

Then on April 4, 1958, the city of Detroit sells the property containing the Conner Creek Cemetery to the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) via quit claim deed. MDOT ends up building a freeway interchange over a portion of the cemetery. The construction of the (Edsel) Ford Freeway, which jaggedly divided the area, facilitated the unearthing of more remains.

Nearly two more decades passed without any press or acknowledgement.

Then, on October 16, 1976, a boulder-plaque was officially placed at the intersection of Conner St & Hern St to commemorate the Conner Creek Cemetery, which was listed as having 4,518 known graves at the time. “It is the only cemetery belonging to the Michigan State Highway department. Many bodies now rest under the roadbed of Conner Street.” (Detroit Free Press article).

The boulder-plaque was courtesy of the Michigan Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

In April 2013, MDOT archeologists and their Pavement Evaluation Unit performed spot excavations and used ground penetrating radar (GPR) to investigate the subsurface of the Conner Creek Cemetery. They found “clearly defined subsurface anomalies, indicative of dense, solid objects.” However, the soil profile (ie: moist silt) in that particular area makes it essentially impossible to use GPR accurately.

Currently (October 2021), the triangle patch of land with the boulder-marker is still there at Conner and Hern. To get there, plug in the address 6008 Gunston Ave, Detroit. This is the neighborhood where Ravendale meets Chandler Park on the NW side of the Chandler Park Golf Course, which itself has been there since the 1920’s (most likely 1923).

Thanks to the amazing efforts of Dr. Karen Krepps, this area has been designated as an archeology site #20WN383. In 1984, she was commissioned by the Eastern Wayne County Historical Society (EWCHS) to write a report about the cemetery. Her report is fascinating, highly detailed and insightful, and I especially agree with her assertion that “cemeteries are important cultural resources.”

Big Question:

Are the various unclaimed human remains still there? Nobody knows.

However, on page 46 of her report, Dr. Krepps states, “The prime area has enjoyed minimal below ground disturbance and may well contain human remains reinterred from the Russell Street Cemetery.”

What ended up happening with the old Russell Street Cemetery property? Let’s take a look.

Some Eastern Market History

After the dismantling of the Russell Street Cemetery, Eastern Market gradually came into being and transformed the area.

By 1885, there was a small market and scales for weighing produce at the NE corner of Division and Russell.

Eastern Market was created in 1889 when the Detroit Common Council formally established the boundaries of the Eastern Hay Market, also known as the Hay and Wood Market.

The construction of Eastern Market’s Shed 1 (Russell St, between Winder and High St) by Richard E. Raseman, was completed in September 1890. It was tiny, supposedly only 575 x 208 feet, rickety and was destroyed in a violent storm on December 23, 1890.

Shed 1 was rebuilt in 1891 and lasted until 1967 when the creation of the Fisher Freeway forced the shed to become a parking lot. In 1898, Raseman built Shed 2.

Shed 3 was built in 1922 as an “all-weather shed”. Shed 4 was constructed in 1938 and Shed 5 in 1939. They are connected by a covered walkway. In the 1950’s, Rosie the Riveter (real name Rose Kurlandsky) ran a produce stand here at Eastern Market. Her stall was located across from the Samuel Brothers Deli.

In 1965, Shed 6 is built. It’s a long, narrow shed with a roof and no walls.

In 1980, the original Shed 5 is demolished and a new Shed 5, along with a 2-story parking structure, are built in 1981. All of the Sheds were majorly renovated in the early 2000’s.

To this day, Eastern Market is a major cultural attraction in the city of Detroit, visited by millions of people annually.

Final Thoughts

In 1834, when the Russell Street Cemetery was created, Detroit had a population of around 5,000 people, according to census data. By the time the cemetery officially closed in 1882, Detroit was a rapidly expanding metropolis with a population of around 150,000 people.

Big cities have fascinating histories and trajectories. They tend to expand so rapidly that many of the historical facts and stories are lost to time and never fully recovered.

Detroit’s very first cemetery was located behind St. Anne’s log church at the NW corner of Jefferson and Griswold. This cemetery was functional 1701-1760 and consisted mostly of French Catholics in mostly unmarked graves. The cemetery moved several times after that.

Are some still buried there? The probability is high that there are indeed still human remains there. Such is the case with any large city. All big cities are dotted with random buried corpses from centuries past, hidden under modern-day structures like skyscrapers and apartment buildings.

Is this true of all early cemeteries? Were ALL the graves exhumed and relocated? Or are some still hidden down below, awaiting discovery?

The unclaimed dead from the Russell Street Cemetery. The nameless who were buried, most likely multiple bodies per grave, in the Conner Creek Cemetery, who were they? Where are their bodies at this exact moment?

Whatever may happen or not happen in the future, PLEASE RESPECT the land and the remains.

Where did you find this information?

Libraries, mostly, and some online repositories. I love libraries. As a lifelong library enthusiast and haunter of book collections, I highly recommend everyone spend more time at these sanctuaries of knowledge. Leave your phone in the car. It’s a good respite from the endless overwhelming digital switch-tasking bombardment perpetually fragmenting your time and sanity.

The bulk of this information was derived from poring over hundreds of vintage Detroit newspapers, along with heavy digging inside the Library of Michigan, the State of Michigan’s main library, in Lansing. Shout out to librarian, Adam Oster, for helping this wayward lad track down some primary source material. I would’ve been at the DPL’s Burton Collection in Detroit talking Mark Bowden’s ear off, but they’ve been closed for a while, first Covid, then flooding. Hope to explore upon their glorious re-opening.

Big thank you to the State Historic Preservation Office (archeologist Michael Hambacher) for providing Dr. Krepps report. And, to MDOT state archeologist James Robertson, for his kindness and alacrity on the FOIA request.

Thank you to Patrick Shaul at the Detroit Society for Genealogical Research for tracking down and scanning the incredibly hard-to-find 5-part article by Detroit archeologist Charles Martinez.

Thanks also to MDOT’s FOIA coordinator Fae Gibson for sending me a disc containing several key documents.

Also, this article is a work-in-progress. Please fact-check me and help me update it. If you have any pertinent and critical information, please email me at place313 at gmail dot com. Thank you!

Bibliography

Krepps, Dr. Karen Lee. Land Use History of Conner Creek Cemetery (20WN383) Containing as Well Background Studies of Clinton Park and Russell Street Cemeteries in Detroit, Wayne County, Michigan. K.L. Krepps, 1984.

Burton, Clarence & Agnes. History of Wayne County & the City of Detroit. Vol 2. SJ Clarke Pub. Co., 1930.

Caitlin, George & Robert Ross. Landmarks of Wayne County and Detroit. Detroit, Evening News Association, 1898.

Clohset, Virginia C. The Detroit City Cemetery in Grosse Pointe. Self-made, 1976. (this detailed 64-page report can be FOIA’ed from MDOT)

Detroit Free Press archives.

Detroit News archives.

Farmer, Silas. History of Detroit and Michigan. Detroit, S. Farmer & Co, 1889.

Fogelman, Randall & Lisa Rush. Detroit’s Historic Eastern Market. Arcadia, 2013.

Hershenzon, Gail. Detroit’s Woodmere Cemetery. Arcadia, 2006.

Krepps, Dr. Karen Lee. Land Use History of Conner Creek Cemetery (20WN383) Containing as Well Background Studies of Clinton Park and Russell Street Cemeteries in Detroit, Wayne County, Michigan. K.L. Krepps, 1984. (this incredibly difficult-to-obtain report can be located at the State Historic Preservation Office).

Lazar, Pamela. Directory of Cemeteries in Wayne County. Dearborn Genealogical Society, 1982.

Maps (assorted).

Martinez, Charles. “Death Defiled: The Calamity of Russell Street Cemetery.” The Detroit Society for Genealogical Research Magazine, vol. 63-64, Spring 2000-Winter 2001. (this hard to find 5-part article can be purchased via the Detroit Society for Genealogical Research).

Palmer, Gen. Friend. Early Days in Detroit. Hunt & June, 1906.

Detroit Free Press newspaper clippings (and some Detroit News clippings):

*These are screenshots of newspapers Detroit Free Press and Detroit News mainly, along with a few other papers. The ones not marked are Detroit Free Press.

January 09, 1838 (entry for James Witherell from the Biographical Directory of American Congress)

May 01, 1870

At this time, the Eastern District hay and wood market was on Hastings Street.

November 02, 1870

February 02, 1871

July 29, 1873

“At a late hour Saturday evening, some boys discovered a man disrobing himself near the Russell Street Cemetery. When they approached, he attacked them vigorously. The next morning he was discovered in the cemetery. He jumped up from behind a tombstone and fired shots from his revolver. He was not wearing any clothes and went running down Russell Street.”

September 17, 1874

“A dreary spot. The Russell Street Cemetery is one of the most dreary and neglected spots in Detroit. Scraggy trees, rank weeds, broken tombstones and sunken graves meet the eye everywhere, and the fences are falling down and going to decay.”

January 30, 1875

An old horse of an ash collector fell while pulling his wagon. He fell in front of the cemetery and was flogged by the owner so badly that someone came up and shot the horse in the head to put it out of its misery.

May 29, 1875

“Condemned as a public nuisance and recommending it’s abatement.”

April 15, 1876 (from the Detroit Daily Advertiser)

May 02, 1876 (from the Detroit Daily Post)

May 04, 1876

“Oscar Davis tries to steal a human skull at the Russell Street Cemetery but is caught and arrested.”

November 23, 1876 (from the Detroit Daily Advertiser)

April 26, 1877

George Moorehouse (9) got his left eye knocked out by a spear while hunting for frogs with a group of boys inside RSC.

August 22, 1877

1878

Alderman Youngblood states that the city wants to make Russell Street Cemetery the location of Eastern Market.

October 20, 1878

Proposals for disinterring bodies from Russell Street Cemetery and re-interring them at Woodmere Cemetery are entertained by William Purcell, president of the Board of Public Works.

October 03, 1879

In one of the graves, 3 corpses were found, “believed they were victims of cholera and buried in haste”

October 29, 1879 (DFP, page 5)

special thanks to Eloise for this article

October 30, 1879

November 14, 1879

“A pile of old coffins, which were dug up last week, presents a ghastly sight in the old RSC.”

November 18, 1879

Germans want to hold Saengerfest (a type of choir singing festival) on the old RSC grounds.

November 22, 1879

November 12, 1880

Still digging up bodies. Body removal is funded by “collection of city taxes”.

October 04, 1881

Bid to disinter bodies and re-inter them is awarded to Hugh Fallon who says he will do it for 93 cents per body and 25 cents per fence.

October 31, 1881

“An interesting discovery was made on Saturday in the old RSC, where the work of digging up the dead is in progress. Two bodies were found to be petrified and in a natural state with the exception of the heads, which had crumbled into dust.”

November 03, 1881

January 11, 1882

October 26, 1882

Contract for removing 1400 bodes to the City Hospital in Grosse Pointe. Disinterred at 100 per day, being done under the direction of the Board of Public Works. Reinterred at City Hospital Grounds GP.

October 30, 1882

November 03, 1882 (Detroit News)

“Some coffins are very primitive. One was made of sidewalk planks. The remains of a very small body were found inside a soap box. The depth at which they’re buried varies greatly. Some are a foot and a half under the surface, others are 6-7 feet. Some bodies are missing (from coffins). Students having snatched them for dissecting purposes.”

February 14, 1883

“The remains of 1,357 bodies were removed from the Russell Street Cemetery to the City Cemetery Grounds at Grosse Pointe at an expense of $1,153.10”

May 30, 1883

September 04, 1887

August Stahlman (Grosse Pointe) farm 36 acres, 2 acres used for bodies from the Russell Street Cemetery, “several thousand skeletons removed from Russell Street Cemetery”.

June 15, 1898

“Laborers brought up a decayed coffin containing a skeleton while excavating for drainage pipes for the new Eastern Market on the old Russell Street Cemetery”.

June 14, 1902

Human bones are found while digging at the old Russell Street Cemetery grounds.

April 22, 1906 (Detroit News)

The city of Detroit owns 34-acre farm in Grosse Pointe. “The farm is rented by a tenant, August Schultz, who has occupied the property for 20 years. It was bought by the Detroit board of health October 18, 1872 to be used as a site for a pest house, or contagious disease hospital.”

June 30, 1910

October 06, 1950 (Detroit News)

“A page of Detroit’s past has been rudely opened by a gang of workmen who have uncovered an ancient cemetery while extending an electric cable pit along the Gunston playground between Harper and Conner avenues.”

May 23, 1967 (DFP page 3-A)

special thanks to Frank Castronova for sending this article over

November 19, 1978

Assorted Maps and Images

Map from Dr. Krepps 1984 report Land Use History of Conner Creek Cemetery (20WN383) Containing as Well Background Studies of Clinton Park and Russell Street Cemeteries in Detroit, Wayne County, Michigan. K.L. Krepps, 1984.

Map from Dr. Krepps 1984 report Land Use History of Conner Creek Cemetery (20WN383) Containing as Well Background Studies of Clinton Park and Russell Street Cemeteries in Detroit, Wayne County, Michigan. K.L. Krepps, 1984.

Recent Comments